Nocturne Table of Contents and Personal Masterlist

My Old Attempt at a ThematSic Analysis

General Concepts of Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne

Character Analyses of . . .

Hikawa

Yuko Takao

Isamu Nitta

Chiaki Tachibana

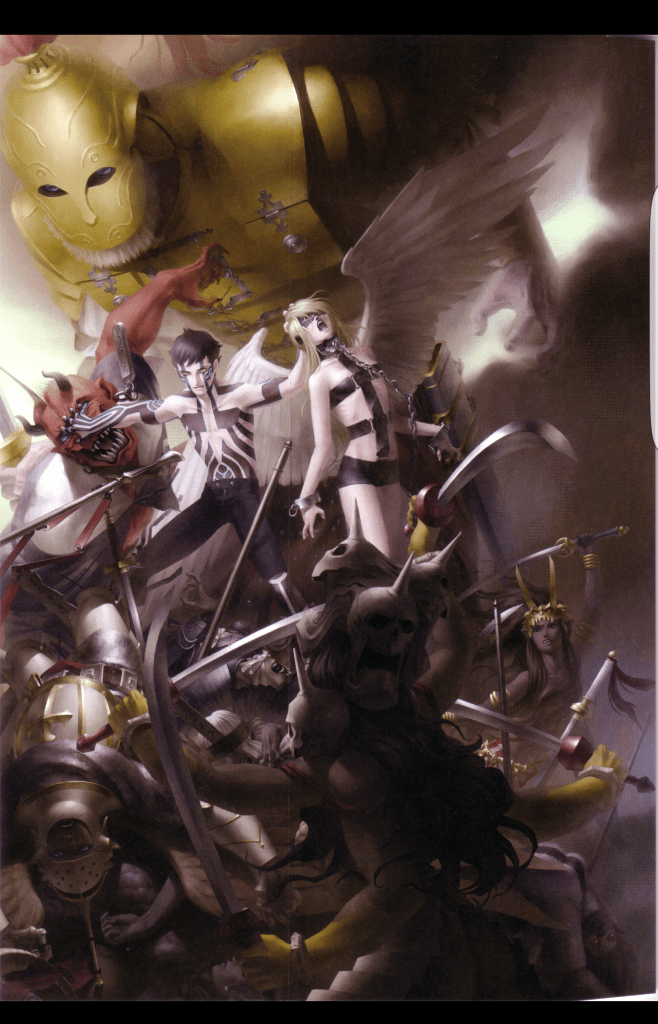

Demi-Fiend

Christian Kabbalah References:

The Qliphoth References (From Debunking Series)

Personal Theories and Arguments:

The Manikins represented Fascism in its most pathetic form

My Opinion Piece on the Musubi Route

Why Hijiri is probably either Aleph or Mormon Jesus Christ

What TDE Raidou Route Means and Why it is my favorite

The Axiom / Great Will is probably some form of Brahman

Please note: The Red lines with underline scores are links that you can click, if you wish to read the source and this will obviously contain major spoilers for Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne.

This will be my attempt at building a more comprehensive and thorough analysis of Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne’s themes. Unlike my previous attempt, I’ll be using the newly updated HD Script because it is more faithful to the Japanese text according to Atlus West’s translators. If you’re familiar with my previous blog posts, you’ll know that this analysis will contain references to the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. There’s been some claims by certain people that it has nothing to do with Nocturne, even going so far as to argue the Atlus West staff is somehow wrong by citing them saying Nocturne has Nietzschean themes, and here is all I’ll say on the matter as I need to stop myself from participating in such a farce any further, because it is not worth it. If you’re familiar with my work, you know where I stand on such issues, and I want to make clear that while I do see Nietzsche’s philosophy in Mainline SMT, I don’t see it in any of the other subseries by Atlus Japan in the context of the greater whole of the Megami Tensei franchise. At best, the music title for one of Catherine’s songs has a reference to the music, Also Sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss, whose music piece was a tribute to Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical fantasy novel, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (titled Also Sprach Zarathustra in German). Needless to say, I wouldn’t write essays if I didn’t see Atlus Japan clearly using the philosophy, something the Atlus West staff has confirmed that is in Nocturne.

For those interested in more “Eastern” philosophy – although I don’t call it Eastern as that erroneously conflates Dharmic philosophy and mythology with the Abrahamic philosophy and mythology of Islam, which is seen as ridiculous by the majority of both sets of religious communities – then, prospective readers will be happy to know that I’ll be referring to a lesser-known minor Upanishad within Hinduism. I’ve noticed some have been eager and hopeful for me to write on such topics, and my main fear was that I was applying my own set of religious values which I thought perhaps Atlus Japan didn’t intend on and consequently, I also feared the more obscure texts in Hinduism would be missed as references since I’ve mainly read a sanitized version of the Upanishads, two different versions of the Bhagavad Gita, the Arthashastra, a few portions of the Rig Veda, a few chapters of the Ramayana, and several stories within the Mahabharata but my main focus has always been the atheistic philosophies within the Samkhya school of Hinduism (in particular, the Samkhya-Karika which I read twice) as of now and I’m fairly sure that Atlus Japan would probably only reference the Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism as it’s the most popular form of Hinduism in modern times and Atlus Japan can surely derive great inspiration from it. Anyway, I’ve found some intriguing evidence that SMTIII: Nocturne draws from an ancient funerary teaching in one of the minor Upanishads, the Kaivalya Upanishad. I’ll be citing it along with Nietzschean philosophy. Also, I have already written two blog posts regarding the Christian Kabbalah symbolism in Nocturne, which I’ve linked to in the Table of Contents.

I would like to make it clear that this is just my own subjective views on Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne. After the four full playthroughs on PS2 which went Shijima, TDE, TDE, and Musubi; with two alternate save-file playthroughs for Yosuga at the point prior to the TDE decision in Nocturne; and a complete 100% playthrough of Nocturne HD Remaster on Hard Mode; I’ve come to the conclusion that Nocturne has an anti-Buddhist and anti-Christian slant that coincides with a Pro-Nietzsche and surprisingly, Pro-Hindu perspective. Although the lens in which Atlus utilizes and designs the artwork for these concepts have a distinctly Buddhist flair likely due to their own Japanese upbringing, it doesn’t change or distort my own observations that Nocturne is quite explicitly anti-Buddhist, even more so than its anti-Christian themes. Whereas its anti-Christian themes are explicitly in the True Demon route, the anti-Buddhist themes are from the very start of the game and throughout the entire main story involving Hikawa. From the moment the world blows-up because of a Buddhist prophecy to Hikawa’s own views mirroring Nietzsche’s criticisms of Buddhism. I was a bit wary of going into this, because I feared that I’d been misreading or misunderstanding due to my own Hindu background, but I don’t think that is the case anymore after reading the Kaivalya Upanishad, reading the theological concepts derived from it by Hindu theologians, and observing the parallels within Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne itself.

However, I would like to make it clear that my perspective on these games, after playing them repeatedly, is that the religious and occult references only exist as a backdrop for the philosophical themes throughout this series. From what I’ve been told by pro-Law enthusiasts, Law is based on Utilitarianism, Chaos is either Survival of the Fittest or Nietzsche with Buddhism more as a backdrop sometimes, and Neutral is somewhat all over the place depending on the individual game, but usually derives its ideology from some nebulous belief in hope that coincides with believing in a delusion about the future without any effort in critical thinking. If anyone is curious regarding my reasoning why I believe the religious metaphors are secondary to the philosophy, one example is the Law alignment itself; if it did intend to have its religious overtones emphasized above the philosophy of Utilitarianism, then why doesn’t it display the misogyny of Biblical teachings? For all the whining about Atlus Japan depicting the Abrahamic faiths poorly, they’ve never depicted the rampant misogyny of all three Abrahamic faiths. The reason being that the Abrahamic mythology is a backdrop for the philosophy of Utilitarianism in most of these games when Law is an alignment choice. With all of that said, I hope you enjoy.

What is the term Nocturne referring to in the title of the game? Most people would probably assume it is the dark atmosphere, even though Kagutsuchi is a Sun deity that floats at the center of the egg-like Vortex world. However, the answer is surprisingly straightforward and answered by the second definition of the term Nocturne:

Nocturne

noun.a dreamlike or pensive composition (usually for the piano)

It’s referring to the Reason choices throughout the game. Each has a piano-centered dreamlike expression while giving you the personal philosophy that each of the characters’ have chosen to follow as their Reason when they ask you if you agree with them or not. The exception to this is Aradia, who isn’t a Reason Sponsor, who has a plainer piano composition, where she asks you to simply choose your own path. This is probably a pleasant surprise for most who wondered just why Nocturne was given its name and what its significance was in the game. As it turns out, it simply meant choosing among the three Reason Sponsors and Yuko Takao in reference to some of the most memorable parts of the game where you decide which ones to agree and disagree with. Some fans seemed to have believed it was an odd reference to the Nocturne music score by Chopin, but it seems that Atlus Japan made a creative reimagining of the definition of the term itself to emphasize the Reason choices throughout the game.

What was the symbolism of the Last Area where you enter the Tower of Kagutsuchi? As it turns out, the straightforward explanations don’t end there. The design of the last area of Nocturne has been given rather bizarre speculation by some uneducated Western fans accusing it of being the Neo-Nazi symbol of the Black Sun. Unfortunately, we Western fans weren’t privy to the Scripture of Miroku opening version of the original Nocturne and only got the Dante re-release version back during the PS2 era. The Scripture of Miroku refers to a Palace in the East and it was referring to the Imperial Palace of Japan. The area around it seems to have meant to signify the enormity of the distance Demi-fiend himself and the others were traveling to get there.

What do the lyrics of Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne mean? I offer a link to a Youtube video where I cover this, and admittedly have to add a corrected version which is the one I will be linking to. Also, if there’s any “controversy” for the lyrics of Forced / Fierce Battle, please listen to these two versions, one by TGE and the other by a fellow MegaTen fan and Youtuber who ripped the lyrics just as clearly from the old PS2 version.

The General Theology and Philosophy in SMTIII: Nocturne

The three major conceptual frameworks that Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne seems to derive from are Hinduism, Christian Kabbalah, and Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophical fantasy novel, Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Buddhism and Zoroastrianism seem to be depicted within the scope of the last of the three with Zoroastrianism largely as a metaphor for an exploration Nietzsche’s philosophy and Buddhism depicted under Nietzsche’s criticisms of Buddhism throughout his philosophical works – including within Thus Spoke Zarathustra – and not specifically Buddhism itself; although Atlus Japan clearly used concepts specific to Japan when the need arose to further supplement Nietzsche’s criticisms against Buddhism. The two most obvious anti-Buddhist examples in the game: the first one comes right at the start of the game from the world ending prophecy of the Scripture of Miroku (i.e. Future Buddha) causing exactly that. The second less noticeable one is Daisoujou, a spiritual Buddhist figure of Japanese origin, who adamantly demands that Demi-fiend accept the end of the world as part of prophetic destiny and accept his death without struggle. Daisoujou’s words are deliberately made in opposition to Nietzsche’s themes.

General Nietzschean Themes

For this first portion, I would like to ask readers a set of questions so that we have a clear understanding of both Nietzsche and why I believe Nietzsche’s themes exist in Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne:

What is the Will to Power?

Some might think it has to do with some framework of discriminatory violence like what Chiaki did to the Manikins or a cold ruthlessness like Hikawa’s general behavior throughout the game. It seems many people have the misunderstanding that it is about strong people abusing those less fortunate than them due to the many Christian apologist blog posts outright lying about Nietzsche, since it is clear that they never read Friedrich Nietzsche and constantly go on about a horse story that is of dubious authenticity. These are all incorrect. Now, I want to avoid using a lengthy, pedantic quote by Nietzsche; I’d like to simply explain it in a more straightforward and clear response based on my reading of his main books, especially with how Nietzsche framed it throughout the philosophical fantasy novel of Thus Spoke Zarathustra because the idea itself is what is explored in Nocturne:

Think of a possible future where you lose your stable life (whether it is your job or school), you lose all of your close friends (through betrayal or loss), and you lose your entire family to a horrific tragedy. Do you just accept falling into depression? Do you decide to just kill yourself because the world doesn’t seem like it is worth living in? Do you even know what to do with your life from then on? Can you still live a happy life after all of this suffering and tragedy?

Friedrich Nietzsche argued that in this hypothetical context what is needed is a Will to Power; that is, a self-perpetuating selfish desire and self-given life purpose so that you stay affirmed to life and don’t give into the temptation of suicide or self-destructive behavior due to depression. Within Nietzsche’s context, following a Church would be the same as following an impulsive, self-destructive behavior as a result of your losses since you’re letting yourself be used by others because you’re vulnerable. What Nietzsche describes as the solution is to make a personal goal for yourself to follow in life that is intrinsically meaningful to you and gives your own subjective meaning back to the world that you live in; he generally meant artistic pursuits, but it is open-ended enough to apply to nearly any profession in life. By following your own personal goals derived from what is intrinsically meaningful about life to you, you stay away from thoughts of suicide and you are elevated from the “herd” of the ignorant masses filled with “Last Men” who don’t know what they want in life, don’t know where they are going, and oftentimes don’t know how to be happy. Whereas, despite losing all that you loved and cherished, you can continue to find love and meaning in the world by following through with your personal dream goals. This is how the Will to Power essentially leads to the “Ubermensch / Superman” concept of Nietzsche’s in Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

What is the Purpose of the Ubermensch Concept?

Of course, this leads to another potential issue that is examined in the philosophical fantasy novel. If a large amount of people become Ubermensch, then this will surely lead to competition amongst themselves due to conflicting personal goals in opposition to each other. In the context of the real world, Nietzsche would probably have pointed to events such as music competitions, but the context of the philosophical fantasy novel uses metaphors of war and power struggles against fellow Ubermensch succumbing to the stronger within these competitions in order to bring about an improved state of affairs which brings about the creation of the Higher Man or Higher People. To stop themselves from falling into self-destructive habits, the Ubermensch must learn the art of self-surpassing and become judge, avenger, and victims of their own ethical code founded upon their personal desires to continue to follow their personal goals. Within the context of applying this philosophical ideal to real life; should an Ubermensch fail to live up to their goal, then they should use whatever jealousy they feel towards their friends as a sign of what they still yearn to achieve and use jealousy as a motivator to improve and work harder towards their goals instead of demeaning or devaluing their friends. In the context of the philosophical fantasy novel, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the Ubermensch destroy each other in order to impose their own will to power upon the world itself to create a new God and new ethical system for the world to follow in order to eventually bring about the creation of the Higher Man or Higher People.

How Does Thus Spoke Zarathustra apply to Nocturne?

Needless to say, for those of you who have played Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne and remember the contents of the story, you’ve surely already seen how Nietzsche’s concepts in Thus Spoke Zarathustra apply to the game and if this isn’t very good evidence that whoever claims otherwise has been lying to you or doesn’t understand anything about Nietzsche’s philosophy, then I don’t know what criterion of evidence can satisfy you. I’ve given my best effort while trying to avoid being pedantic and I want to keep my commitment on only focusing on the game’s themes. I worry that going by a point-by-point reference would only seem insulting to the intelligence of my readers and I don’t want to do that. I’ll be going into the specifics of how Demi-fiend in the True Demon Route, each of the Reason Sponsors, and Yuko Takao are a critique of Nietzsche’s concepts in Thus Spoke Zarathustra in my character analysis for each of them. However, for the purposes of this essay section, if you don’t find it insulting for me to go on a point-by-point explanation on the general themes and how they apply to Nocturne, I’ll be adding quotes from Thus Spoke Zarathustra and picture quotes from the game itself to show the connections with my explanations of how they apply:

The Metaphors in the Plot

It should come as no surprise for people who have played Nocturne that the hypothetical scenario that Nietzsche described in his lengthy discourses within Thus Spoke Zarathustra used to frame the positives of his Ubermensch concept; imagining someone who has lost everything and asking us to question how they can go on when all external factors that gave them meaning and purpose are gone; fully fit with the introductory events of the Conception in Nocturne. Likewise, forming a Reason, creating a God, and bringing a new ethical system into being through a battle amongst fellow elevated members of humanity are metaphors for exploring the concepts in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Here is the description of the application of the Will to Power in Thus Spoke Zarathustra in contrast to a “Will to Truth” which is the idea that people who grow-up with the old values assume that it is thereby good by default:

XXXIV. SELF-SURPASSING

“WILL TO TRUTH” do ye call it, ye wisest ones, that which

impelleth you and maketh you ardent?

Will for the thinkableness of all being: thus do I call your will!

All being would ye make thinkable: for ye doubt with

good reason whether it be already thinkable.

But it shall accommodate and bend itself to you! So

willeth your will. Smooth shall it become and subject to

the spirit, as its mirror and reflection.

That is your entire will, ye wisest ones, as a Will to

Power; and even when ye speak of good and evil, and of estimates of value.

Ye would still create a world before which ye can bow

the knee: such is your ultimate hope and ecstasy.

The ignorant, to be sure, the people—they are like a

river on which a boat floateth along: and in the boat sit

the estimates of value, solemn and disguised.

Your will and your valuations have ye put on the river

of becoming; it betrayeth unto me an old Will to Power,

what is believed by the people as good and evil.

It was ye, ye wisest ones, who put such guests in this

boat, and gave them pomp and proud names—ye and your ruling Will!

Onward the river now carrieth your boat: it must carry

it. A small matter if the rough wave foameth and angrily resisteth its keel!

It is not the river that is your danger and the end of

your good and evil, ye wisest ones: but that Will itself,

the Will to Power—the unexhausted, procreating life-will.

But that ye may understand my gospel of good and

evil, for that purpose will I tell you my gospel of life, and

of the nature of all living things.

The living thing did I follow; I walked in the broadest

and narrowest paths to learn its nature.

With a hundred-faced mirror did I catch its glance when

its mouth was shut, so that its eye might speak unto me.

And its eye spake unto me.

But wherever I found living things, there heard I also

the language of obedience. All living things are obeying things.

And this heard I secondly: Whatever cannot obey itself, is commanded. Such is the nature of living things.

This, however, is the third thing which I heard—namely,

that commanding is more difficult than obeying. And

not only because the commander beareth the burden of

all obeyers, and because this burden readily crusheth him:—

An attempt and a risk seemed all commanding unto

me; and whenever it commandeth, the living thing risketh itself thereby.

Yea, even when it commandeth itself, then also must it

atone for its commanding. Of its own law must it become the judge and avenger and victim.

How doth this happen! so did I ask myself. What

persuadeth the living thing to obey, and command, and

even be obedient in commanding?

Hearken now unto my word, ye wisest ones! Test it seriously, whether I have crept into the heart of life itself, and into the roots of its heart!

Wherever I found a living thing, there found I Will to Power; and even in the will of the servant found I the will to be master.

That to the stronger the weaker shall serve—thereto

persuadeth he his will who would be master over a still

weaker one. That delight alone he is unwilling to forego.

And as the lesser surrendereth himself to the greater

that he may have delight and power over the least of all,

so doth even the greatest surrender himself, and staketh— life, for the sake of power.

It is the surrender of the greatest to run risk and danger, and play dice for death.

And where there is sacrifice and service and love-glances,

there also is the will to be master. By by-ways doth the

weaker then slink into the fortress, and into the heart of

the mightier one—and there stealeth power.

And this secret spake Life herself unto me. “Behold,”

said she, “I am that which must ever surpass itself.

To be sure, ye call it will to procreation, or impulse towards a goal, towards the higher, remoter, more manifold: but all that is one and the same secret.

Rather would I succumb than disown this one thing; and verily, where there is succumbing and leaf-falling, lo, there doth Life sacrifice itself—for power!

That I have to be struggle, and becoming, and purpose, and cross-purpose—ah, he who divineth my will, divineth well also on what crooked paths it hath to tread!

Whatever I create, and however much I love it,—soon must I be adverse to it, and to my love: so willeth my will.

And even thou, discerning one, art only a path and footstep of my will: verily, my Will to Power walketh even on the feet of thy Will to Truth!

He certainly did not hit the truth who shot at it the

formula: ‘Will to existence’: that will—doth not exist!

For what is not, cannot will; that, however, which is in

existence—how could it still strive for existence!

Only where there is life, is there also will: not, however,

Will to Life, but—so teach I thee—Will to Power!

Much is reckoned higher than life itself by the living

one; but out of the very reckoning speaketh—the Will to Power!”—

Thus did Life once teach me: and thereby, ye wisest

ones, do I solve you the riddle of your hearts.

Verily, I say unto you: good and evil which would be

everlasting—it doth not exist! Of its own accord must it ever surpass itself anew.

With your values and formulae of good and evil, ye

exercise power, ye valuing ones: and that is your secret

love, and the sparkling, trembling, and overflowing of your souls.

But a stronger power groweth out of your values, and a

new surpassing: by it breaketh egg and egg-shell.

And he who hath to be a creator in good and evil—

verily, he hath first to be a destroyer, and break values in pieces.

Thus doth the greatest evil pertain to the greatest good:

that, however, is the creating good.—

Let us speak thereof, ye wisest ones, even though it be

bad. To be silent is worse; all suppressed truths become poisonous.

And let everything break up which—can break up by

our truths! Many a house is still to be built!— Thus spake Zarathustra.” – Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Pages 108 – 111. Thomas Common Edition.

Ubermensch Power Struggles as Friendship

XIV. THE FRIEND

“ONE, IS ALWAYS too many about me”—thinketh the anchorite. “Always once one—that maketh two in the long run!”

I and me are always too earnestly in conversation: how

could it be endured, if there were not a friend?

The friend of the anchorite is always the third one: the

third one is the cork which preventeth the conversation

of the two sinking into the depth.

Ah! there are too many depths for all anchorites. Therefore, do they long so much for a friend, and for his elevation.

Our faith in others betrayeth wherein we would fain

have faith in ourselves. Our longing for a friend is our betrayer.

And often with our love we want merely to overleap

envy. And often we attack and make ourselves enemies,

to conceal that we are vulnerable.

“Be at least mine enemy!”—thus speaketh the true

reverence, which doth not venture to solicit friendship.

If one would have a friend, then must one also be

willing to wage war for him: and in order to wage war,

one must be capable of being an enemy.

One ought still to honour the enemy in one’s friend.

Canst thou go nigh unto thy friend, and not go over to him?

In one’s friend one shall have one’s best enemy. Thou

shalt be closest unto him with thy heart when thou withstandest him.

Thou wouldst wear no raiment before thy friend? It is

in honour of thy friend that thou showest thyself to him

as thou art? But he wisheth thee to the devil on that account!

He who maketh no secret of himself shocketh: so much

reason have ye to fear nakedness! Aye, if ye were Gods, ye

could then be ashamed of clothing!

Thou canst not adorn thyself fine enough for thy friend;

for thou shalt be unto him an arrow and a longing for the Superman.

Sawest thou ever thy friend asleep—to know how he

looketh? What is usually the countenance of thy friend? It

is thine own countenance, in a coarse and imperfect mirror.

Sawest thou ever thy friend asleep? Wert thou not dismayed at thy friend looking so? O my friend, man is

something that hath to be surpassed.

In divining and keeping silence shall the friend be a

master: not everything must thou wish to see. Thy dream

shall disclose unto thee what thy friend doeth when awake.

Let thy pity be a divining: to know first if thy friend

wanteth pity. Perhaps he loveth in thee the unmoved eye,

and the look of eternity.

Let thy pity for thy friend be hid under a hard shell;

thou shalt bite out a tooth upon it. Thus will it have delicacy and sweetness.

Art thou pure air and solitude and bread and medicine

to thy friend? Many a one cannot loosen his own fetters,

but is nevertheless his friend’s emancipator.

Art thou a slave? Then thou canst not be a friend.

Art thou a tyrant? Then thou canst not have friends – Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Pages 60 – 61. Thomas Common Edition.(Please Note: I removed the sexist latter-half that goes onto page 62 as it didn’t seem relevant)

The friends chiefly refer to Chiaki and Isamu throughout the narrative. Certain portions of the quoted passage regarding pity fit Isamu better than Chiaki, because the player may feel either pity or annoyance with Isamu when Isamu is clinging onto Yuko Takao as the answer to his problems within the Vortex world only to get captured and suffer torture twice. Whether players felt annoyed by his stupidity or sympathetic to his plight, Isamu gives up on others and seeks his answers on how to move forward with his life on his own. Regardless of what you choose, if you agree with Isamu’s Reason then he faces defeat at the hands of Chiaki’s Baal Avatar, but if you disagree with his Reason, then he is put down by your own hands. By contrast, the portions about honor fits Chiaki more than Isamu. Chiaki fails of her own accord, never tries to burden you with her problems like Isamu, and elevates herself to a new level of power and immediately asks for your approval of it out of respect and admiration for you. Nevertheless, if you oppose them, both Chiaki and Isamu say farewell to the former friendship with you before proceeding to battle you to the death within elevated forms that rise above their humanity in order so that they may impose their own ethical code for the formation of a new world.

Kagutsuchi

I tell you: one must still have chaos in one, to give birth to a dancing star. I tell you: ye have still chaos in you.

Although I suspect there is more to Kagutsuchi’s design (I can’t help but think of the possibility that AM from “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” by Harlan Ellison might have been an inspiration, but I couldn’t find any proof so any similarities might be a coincidence), the Disco Ball concept was most likely derived from the Dancing Star bringing Chaos in Thus Spoke Zarathustra with the dancing disco-ball styled Kagutsuchi bringing forth a chaotic world as the setting of Nocturne. The star metaphor is mentioned at the end of Thus Spoke Zarathustra where the titular character contemplates its meaning:

“Thou great star,” spake he, as he had spoken once

before, “thou deep eye of happiness, what would be all

thy happiness if thou hadst not those for whom thou shinest!

And if they remained in their chambers whilst thou art

already awake, and comest and bestowest and distributest,

how would thy proud modesty upbraid for it!

Well! they still sleep, these higher men, whilst I am

awake: they are not my proper companions! Not for them

do I wait here in my mountains.

At my work I want to be, at my day: but they understand not what are the signs of my morning, my step—is not for them the awakening-call.

They still sleep in my cave; their dream still drinketh at

my drunken songs. The audient ear for me—the obedient ear, is yet lacking in their limbs.” – Thus Spoke Zarathustra, page 289. Thomas Common Edition.

The sun deity aspect doesn’t discount the reference to a dancing star since the sun is a star. It seems to be infused with another passage in Thus Spoke Zarathustra about glittering all the values possible for humanity, since Kagutsuchi must be defeated by a strong Reason holder to give rebirth to the world:

Its last Lord it here seeketh: hostile will it be to him, and to its last God; for victory will it struggle with the great dragon. What is the great dragon which the spirit is no longer inclined to call Lord and God?

“Thou-shalt,” is the great dragon called. But the spirit of the lion saith, “I will.”

“Thou-shalt,” lieth in its path, sparkling with gold—a scale-covered beast; and on every scale glittereth golden, “Thou shalt!”

The values of a thousand years glitter on those scales, and thus speaketh the mightiest of all dragons: “All the values of things—glitter on me. All values have already been created, and all created values—do I represent. Verily, there shall be no ‘I will’ any more. Thus speaketh the dragon

My brethren, wherefore is there need of the lion in the spirit? Why sufficeth not the beast of burden, which renounceth and is reverent?

To create new values—that, even the lion cannot yet accomplish: but to create itself freedom for new creating—that can the might of the lion do.

To create itself freedom, and give a holy Nay even unto duty: for that, my brethren, there is need of the lion. To assume the right to new values—that is the most formidable assumption for a load-bearing and reverent spirit. Verily, unto such a spirit it is preying, and the work of a beast of prey.

As its holiest, it once loved “Thou-shalt”: now is it forced to find illusion and arbitrariness even in the holiest things, that it may capture freedom from its love: the lion is needed for this capture. But tell me, my brethren, what the child can do, which even the lion could not do? Why hath the preying lion still to become a child?

Innocence is the child, and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a holy Yea.

Aye, for the game of creating, my brethren, there is needed a holy Yea unto life: its own will, willeth now the spirit; his own world winneth the world’s outcast. Three metamorphoses of the spirit have I designated to you: how the spirit became a camel, the camel a lion,

and the lion at last a child.”—Thus spake Zarathustra, Thomas Common Edition, Pgs 33-35.

The Theme of Suffering and How the Game Reflects it

WHEN ZARATHUSTRA HAD spoken these words, he again looked

at the people, and was silent. “There they stand,” said he

to his heart; “there they laugh: they understand me not;

I am not the mouth for these ears.

Must one first batter their ears, that they may learn to

hear with their eyes? Must one clatter like kettledrums

and penitential preachers? Or do they only believe the stammerer?

They have something whereof they are proud. What do

they call it, that which maketh them proud? Culture,

they call it; it distinguisheth them from the goatherds.

They dislike, therefore, to hear of ‘contempt’ of themselves. So I will appeal to their pride.

I will speak unto them of the most contemptible thing: that, however, is the last man!”

And thus spake Zarathustra unto the people:

It is time for man to fix his goal. It is time for man to

plant the germ of his highest hope.

Still is his soil rich enough for it. But that soil will one

day be poor and exhausted, and no lofty tree will any

longer be able to grow thereon.

Alas! there cometh the time when man will no longer

launch the arrow of his longing beyond man—and the

string of his bow will have unlearned to whizz!

I tell you: one must still have chaos in one, to give

birth to a dancing star. I tell you: ye have still chaos in you.

Alas! There cometh the time when man will no longer

give birth to any star. Alas! There cometh the time of the

most despicable man, who can no longer despise himself.

Lo! I show you the last man.

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What

is a star?”—so asketh the last man and blinketh.

The earth hath then become small, and on it there

hoppeth the last man who maketh everything small. His

species is ineradicable like that of the ground-flea; the last man liveth longest.

“We have discovered happiness”—say the last men, and blink thereby.

They have left the regions where it is hard to live; for

they need warmth. One still loveth one’s neighbour and

rubbeth against him; for one needeth warmth.

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful:

they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbleth over stones or men!

A little poison now and then: that maketh pleasant

dreams. And much poison at last for a pleasant death.

One still worketh, for work is a pastime. But one is

careful lest the pastime should hurt one.

One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too

burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth

to obey? Both are too burdensome.

No shepherd, and one herd! Every one wanteth the

same; every one is equal: he who hath other sentiments

goeth voluntarily into the madhouse.

“Formerly all the world was insane,”—say the subtlest

of them, and blink thereby.

They are clever and know all that hath happened: so

there is no end to their raillery. People still fall out, but

are soon reconciled—otherwise it spoileth their stomachs.

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their

little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

“We have discovered happiness,”—say the last men, and blink thereby.—

And here ended the first discourse of Zarathustra, which

is also called “The Prologue”: for at this point the shouting and mirth of the multitude interrupted him. “Give us this last man, O Zarathustra,”—they called out—”make us into these last men! Then will we make thee a present of the Superman!” And all the people exulted and smacked their lips. Zarathustra, however, turned sad, and said to his heart:

“They understand me not: I am not the mouth for these ears.

Too long, perhaps, have I lived in the mountains; too

much have I hearkened unto the brooks and trees: now

do I speak unto them as unto the goatherds.

Calm is my soul, and clear, like the mountains in the

morning. But they think me cold, and a mocker with terrible jests.

And now do they look at me and laugh: and while they

laugh they hate me too. There is ice in their laughter.”

– Thus Spoke Zarathustra, pages 25 – 27. Thomas Common Edition.

Whether depicting Aradia or the Manikins under Futomimi, the depiction of characters who strive after a world without suffering is depicted negatively. The Manikins are allusions to the Last Men; being remnants of a past era, having no purpose in life and no real ability to challenge Kagutsuchi for Creation, having no direction besides clinging to Futomimi as a herd, and misunderstanding Futomimi’s ability to see into the near-future as an ability to observe the future. Futomimi’s ability is a metaphor for only being able to see in the present moment without the ability to fully comprehend the consequences of their own actions when they begin a racial supremacist movement to vie for Creation against the Reason Sponsors. This bias that Futomimi has for the present moment is hinted at within the game itself such as if you speak to Nyx in Ginza prior to Futomimi’s death.

While many Nocturne fans in the West presume that Futomimi and the Manikins are metaphors for the mythology of the Old Testament story of Moses with the fictional Israelites plight against a fictional unnamed Pharaoh in the mythological text known as The Bible, I’m afraid that there’s not as much support for this as they would like to believe. While Nocturne does indeed have three pyramid-styled dungeons, the Manikins aren’t building them via slave labor and they have no association with the Manikins within the context of Nocturne’s story. Futomimi doesn’t seem to have any connection to the story of Moses either; he doesn’t free his people from slavery and torture in Kabukicho Prison like the mythological Moses figure freed the fictional version of the Israelites in the mythological novel of The Bible. The Demi-fiend breaks them free and Futomimi is one of the two specific named characters who are rescued. Perhaps the most crucial factor that made me seriously doubt any connection to Moses is that Futomimi doesn’t will a Reason and then use the Magatsuhi in Mifunashiro to create a God. I honestly think that within the context of Nocturne’s narrative this is a damning indictment on any possibility of Futomimi being a metaphor for Moses, because Nocturne’s setting is one where you create a Reason through sheer willpower and collect enough Magatsuhi to form a God based upon that Reason. If Futomimi was suppose to be a metaphor for Moses, why was there never any metaphor for the Ten Commandments or Futomimi summoning some equivalent to an Abrahamic mythological figure? To add to the issues with the idea he had any metaphorical relation to Moses, the PS2 script sanitized the fascistic elements of his movement unlike the HD Remaster’s more accurate script. You can read about how Futomimi built a fascist cult by clicking here or on the table of contents above. As you can see, my view of it is that they had always been intended to be a depiction of fascism in its most pathetic state. However, if that seems like a misunderstanding on my part, then I would say that at the very least, they likely represented Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of The Last Man since they’re a race of people who get wiped out in all but one ending of the game, they can’t impact the narrative near the end once Futomimi and Sakahagi are both dead and only brought back to become Demi-fiend’s demons in the optional Amala Labyrinth, Futomimi’s desire for a world without suffering was delusional, and the revelation by the Lady in Black is that the Manikins are intrinsically worthless as a race. It is because they largely cannot create; they are metaphors for people without any direction or passion in life who are easily swayed with resentment for those more powerful than them. They cannot find a purpose or a meaning for their existence, they flitter about being abused and crying about their troubles but don’t work out realistic solutions, they cling to extremist leaders as a herd and seek delusional ideal worlds that would cleanse those that are different from them, and they don’t have what it takes to create beyond themselves by forming new ethical meanings that would give them a goal in life. Above all, they see suffering as a nausea and not as a means to better themselves or to correct themselves by learning from misfortune. When they seem in need, then some players pity them, but when they gain power then they seek to destroy others for their own narcissistic proclivities of making the world as pitiful as them and thereby degrading it into squalor. Even the argument about their equality is questionable, because their equality is predicated upon following Futomimi’s near-sighted whims and that isn’t a stable or equal future for anyone.

However, there is one Manikin who rises above all of that and presents Ubermensch qualities. It is not either Futomimi or Sakahagi; it is the Collector Manikin. Whereas the others live to serve Futomimi’s near-sighted whims, the Collector Manikin lives for the passion of his hobby of collecting things. Whereas the others suffer and perish at the whims of the strong that they challenged in a war, the Collector Manikin keeps himself busy in his shop and doesn’t care what the rabble of his own race outside are doing because he’s too busy living a satisfying life working his dream goal as a shopkeeper and continuing to use it to fund his hobby as a diehard collector of the old world. Once it is all said and done with the arc of the Manikins, only the Collector Manikin stands equal with the Demi-fiend and it is in the True Demon Route that this is so. The Collector Manikin stands in contrast to Sakahagi and Futomimi and the rest of his own kind. Whereas the herd follow Futomimi and Sakahagi lives only for his lust for violence and his desire to rule as a tyrant by controlling a strong demon, the Collector Manikin simply lives his dream goals without worrying about what others are doing, how he is seen by his wider community, or what horrible state of affairs that they get themselves into. Even if the world perishes and he with it, he has lived his best life possible. The true meaning of an Ubermensch who follows their personal goals. It exemplifies a lesson for people in real life; we must all come to terms with the reality of our own mortality, so we may as well work towards fulfilling our personal dreams while we still exist.

Aradia is no less a reflection of this theme. In the original PS2 translation, she was referred to as a Goddess of Falsehood and in the more accurate HD Script, she’s referred to as the Goddess of Forsaken Freedom. I’ll be giving more details about her in the Yuko Takao Character Analysis; for the purposes of this section, I wanted to point out how she further reflects the theme of failure because she doesn’t suffer for her meaning. What seems like Demi-fiend choosing the “sane” option is a misapprehension that doesn’t fit either the religious or philosophical themes of Nocturne and I would ask that players consider one of the chief problems: looking up the Human Freedom ending and automatically assuming that it is the “Good” ending biases people into not really looking into the details of the other characters or their views. A person who has watched the ending before playing the game is more likely to assume that everyone else is crazy because they don’t side with Yuko Takao . . . when in fact, nobody knew the world could be reset back to how it was. I’ve even seen people rename Chiaki “dumb” on Youtube and it seems like a fundamental failure at understanding the positions of the characters. Literally nobody in the game knew that the previous world could come back and the Human Freedom ending itself presents it as almost an accident forced by the sheer willpower of the Demi-fiend using an Unnamed Reason upon defeating Kagutsuchi. I just can’t help but wonder if people who watched the game endings on Youtube and automatically assumed one ending was good and the rest were “crazy” have fundamentally failed at understanding this game. Players weren’t even supposed to know that Young Boy and Old Man Lucifer were the same person; Lady in Black refers to the Young Boy as if speaking of someone else. Some might scoff at that idea, but without Youtube, you could never be one-hundred percent sure and there was a sense of unease without having looked up the endings on Youtube.

The reason I brought all of that up is so that you all understand that my interpretation of the game and the interpretation that Neutral could potentially be a bad ending is not some deluded, harebrained idea. It’s equally as valid as the people who prefer the Neutral ending of the game. What you should note in the case of Aradia is that she doesn’t help at all; you do all the work, you suffer in her stead instead of either Takao or Aradia working to actually improve themselves, and you get an ending that seems good at first glance, but has severe consequences written in the scenes. The fact Hijiri also came back and he’s cursed to witness the death of the world means it is still oncoming in Demi-fiend’s lifetime and you’ve only delayed it for a short while. Ah! But that’s just a Maniax addition to the narrative despite Lucifer’s words also supporting that idea in the Freedom ending itself, right? Well, I hope you look forward to my examination of what Yuko Takao and Aradia represent within the context of their Character Analysis. It was the most enlightening understanding and may explain why I, a person from a Hindu background, have been averse to Yuko Takao’s route and critical of her character even prior to being more aware of what she represented in the Dharmic context. Nevertheless, the fact you had to do all the work, and endure all the suffering, should key you in on what Aradia and Yuko Takao represented.

General Dharmic Concepts

That is why the Vortex resembles a sphere.

KK: Well, it is already thought that the Universe has that type of a bubble like structure. There are these kinds of things in the Universe whose surface resembles an eggshell, but are empty on the inside. We don’t really know what they’re really like though. They may be fractal structures similar to mandalas. There’s something on the inside, which is divided into other parts…something like that.

If we take current universe theories into consideration, they end up looking identical to Hindu philosophy.

KK: It’s interesting if you think about the myths and the outlook on the universe together. If you take Hindu philosophy to the extreme, everything ends up being Vishnu through fractal structures.

We encounter the same worldview in Gnosticism.

KK: Yes, yes. Gnosticism has the fractal structure view as well. In their outlook on the universe, first there was a sphere, then another sphere, and so on. In the center of the mandala lies Mount Sumeru, then there are several layers with several creatures…They’re similar.

Within theistic Hinduism, it is generally believed that the cycle of death and rebirth (Samsara) is something all people go through via reincarnation and that by following Dharmic duties, they will eventually gain self-liberation (Moksha) and become one with Brahman. As some of you may know, Buddhism has a similar concept in nirvana. Without getting too pedantic, this concept applies to the world itself in certain theistic Dharmic concepts (like Mahayana Buddhism such as Tibetan Buddhism). Within Nocturne, the Conception brings about the death of the old world in order to create a competition to bring forth the birth of a new world and we learn in the earliest of the Amala Labyrinth explanations that this is an ongoing and seemingly endless cycle that exists across billions of alternate universes. Note that, whether you agree with the Human Freedom or TDE / Rejection route as the best ending, both routes are opposed to this cycle and depict it negatively.

The theological concepts in Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne seem to chiefly cover Hinduism’s Kaivalya Upanishad, specifically with Buddhism presented in opposition. I had initially considered that the Three Reasons represented the Three Gunas of Hinduism, without becoming too pedantic the three Gunas are a concept of three specific qualities that pervade all of reality that in some schools of Hindu thought state that a person must keep in balance to achieve self-liberation (Moksha) and this concept originates prior to the current dominant viewpoint of Advaita Vedanta in Hinduism, but after reading of the Vedanta concepts affiliated with the Kaivalya Upanishad, I’ve concluded that it was derivative concepts of the Three Gunas formed in the Kaivalya Upanishad that SMTIII: Nocturne was referencing that better reflect from the character development and Reasons of Isamu, Chiaki, and Hikawa. I concluded this due to two of the Three Gunas not properly reflecting two of the Reason characters in certain translated descriptions of them. However, I’d figure that I share the basic definitions mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita because they might be a good starting point to understand the concepts derived from them that Nocturne does reference:

If Atlus Japan was indeed using these basic definitions as a starting point, then Chiaki depicted Rajas, Hikawa depicted Sattva, and Isamu depicted Tamas. However, due to the plot involving the absorption and use of negative human emotions of Magatsuhi, they are reflected only in their most extreme and negative forms in the game itself. Defeating the Reason Gods in routes when not aligned with them represents putting them back in balance either for the sake of the world in the Human Freedom route or for affirming self-transcendence in the True Demon / Rejection route. Whereas in the Three Reason Endings, the theming suggests that Demi-fiend has given himself to an illusory world through the depiction of the shadowy rising cities at the end of every Reason ending. Within the context of the Kaivalya Upanishad, the descriptive term of three competing cities is used as an analogy to describe how each of the three dream-like derivatives of the Three Gunas fight to suppress the other two and keep a person within the bondage of the physical world and the cycle of death and rebirth (Samsara). They’re viewed as the substratum (that is, the underlying foundation) of the world itself gone to an extreme. This neatly fits with what happens within each of the Three Reason Endings; you defeat the other two (and in Yosuga, you defeat all three for the sake of consistency with Yosuga’s ideology and this is actually emblematic of the derivative of Rajas going into a negative extreme and not a counterpoint against it), to participate in the way of Creation and continue the cycle of endless deaths and rebirths of the world that you exist within. Unfortunately, it would be impossible for me to go into the specifics on what those derivatives are without delving into each of their characters, so that’ll be for the next Nocturne Analysis focusing on the specific themes of each of the prominent characters. I hope you look forward to it.

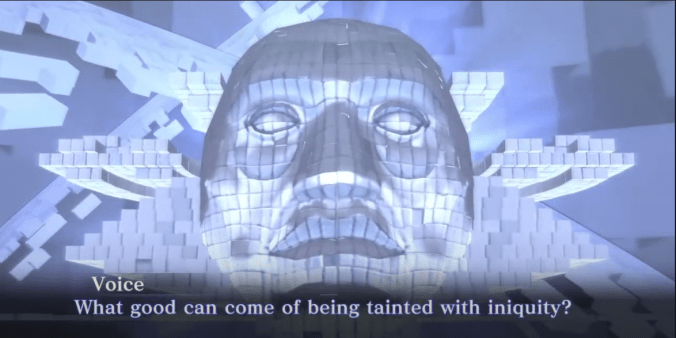

But for now, let me leave you with my favorite Thus Spoke Zarathustra quote and what made me convinced Thus Spoke Zarathustra was connected to Nocturne:

“What is the greatest thing ye can experience? It is the hour of great contempt. The hour in which even your happiness becometh loathsome unto you, and so also your reason and virtue.

The hour when ye say: “What good is my happiness! It is poverty and pollution and wretched self-complacency. But my happiness should justify existence itself!”

The hour when ye say: “What good is my reason! Doth it long for knowledge as the lion for his food? It is poverty and pollution and wretched self-complacency!”

The hour when ye say: “What good is my virtue! As yet it hath not made me passionate. How weary I am of my good and my bad! It is all poverty and pollution and wretched self-complacency!”

The hour when ye say: “What good is my justice! I do not see that I am fervour and fuel. The just, however, are fervour and fuel!”

The hour when we say: “What good is my pity! Is not pity the cross on which he is nailed who loveth man? But my pity is not a crucifixion.”

Have ye ever spoken thus? Have ye ever cried thus? Ah! Would that I had heard you crying thus! It is not your sin—it is your self-satisfaction that crieth unto heaven; your very sparingness in sin crieth unto heaven!”

“Where is the lightning to lick you with its tongue? Where is the frenzy with which ye should be inoculated? Lo, I teach you the Superman: he is that lightning, he is that frenzy!”

– Friedrich Nietzsche, “Thus Spake; Zarathustra” Page 23. Thomas Common Edition.

For more on Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne:

Kaneko Interviews:

Demon Bible, 1UP Interview regarding Nocturne (Red Hot Chili Peppers as inspiration and Gnostic view of the world as inspiration for Nocturne) and Kazuma Kaneko Works III / Different Translation.

Non-SMT3 Interviews or Artbook Translations: SMT NINE Demons in Kaneko Works III (Eternal Recurrence Concept of Nietzsche referenced in Maria bio), Kaneko Works I, and Kaneko Works II.

From Atlus West: Atlus West Interview with Vice on how they translated the HD Remaster Script

Fan Content by Others

Other Blogs:

Philosophy of MegaTen Encyclopedia by Beadman

Sam Hatting’s Nietzschean themes in Nocturne (that inspired all of this)

SMT Nocturne and Space in Design by LazyMetaphors

Artemis-Maia Analysis of Amaravati and the Menorahs (that inspired my Qliphoth References) on Eirikrjs Blog

Youtube Content Creators:

SMT Theology by Kid Capes

Larrue’s Nocturne videos related to Themes and Development:

- Story of SMT Nocturne

- Lost SMT3 Nocturne’s Early Draft Concepts

- Kazuma Kaneko’s Art Team

- Learning more about Kazuma Kaneko

Deconstructing Nocturne’s Formulas by Robin and Zephyr

Rasen Bran’s Cathedral of Shadows Podcast:

Season 1, Season 2, and Season 3

Fither’s Lost Nocturne Tech Demo

The 4th Snake’s Opinion Piece on Nocturne’s Freedom Ending

Pingback: A Thematic Analysis of Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne | Jarin Jove's Blog

Pingback: Shin Megami Tensei III Nocturne Theory: Who Was the Lady in Black? | Jarin Jove's Blog

Pingback: My Thoughts on the Megami Tensei Franchise and Community | Jarin Jove's Blog

Pingback: Why Hijiri is probably either Aleph or Mormon Jesus Christ | Jarin Jove's Blog

Pingback: Debunking the “Tragic Asshole”: Eirikrjs Lied about the Kabbalah References in SMT Nocturne | Jarin Jove's Blog